News

WHAT IS IVA?

IVA is a tax on the final consumption of goods and services that is collected at each stage of the production and distribution process. From the buyer's perspective, IVA is a tax on the purchase price. From the seller's point of view, the IVA is a tax on the value added (hence it is called a value added tax) at this point in the production/distribution chain.

IVA is a tax on the final consumption of goods and services that is collected at each stage of the production and distribution process. From the buyer's perspective, IVA is a tax on the purchase price. From the seller's point of view, the IVA is a tax on the value added (hence it is called a value added tax) at this point in the production/distribution chain.

Each actor in the chain has the right to deduct IVA on the materials/services it buys and the duty to pay IVA on the sale. The firm simply remits to the state the difference between the IVA charged on sales and the IVA paid on purchases. This process is called the clearance mechanism and can be presented with the following formula:

VAT cleared = (Sales value x IVA) - (Value of purchases x IVA)

Or

Input VAT = IVA (Sales Value - Purchase Value)

As you can see, IVA is applied on the gross margin (Sales Value - Purchase Value), i.e. the value added at each step of the chain.

From a practical point of view, IVA works like a sales tax in that only the final consumer is taxed. The big difference is that with a sales tax, all tax is collected at a single point in time: the final point of sale. With a IVA, the tax is collected along the chain at each moment when value is added to the product. At the end of the process, the result is the same: only the final consumer pays, and the companies that are part of the process do not suffer any direct impact from the tax.

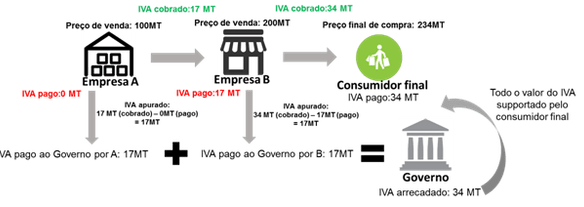

Here is an illustration of how VAT works. To simplify the example, the first actor (Company A has no inputs subject to IVA:)

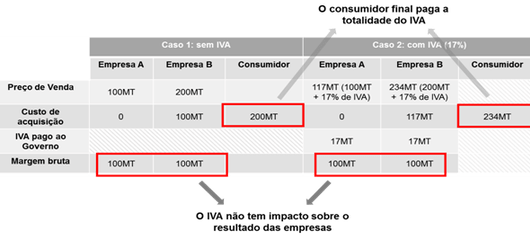

In the example above, each actor remits to the government the difference between the VAT it pays (the VAT it deducts) and the VAT it collects (the VAT it liquidates on sales). The consumer is not entitled to recover the VAT, but bears all the tax, so VAT is called a consumption tax. It is important to note that the actors in the chain, Company A and B, only served as a transmission mechanism and do not suffer any direct impact of taxation. To clarify, we compare the same case with and without VAT:

The above examples illustrate a situation where VAT is fully functioning, i.e., all stakeholders pay and are able to pass on VAT. However, in reality, VAT may not function in a linear fashion, due to exemptions introduced by various tax regimes. In Mozambique there are essentially two regimes: the normal regime and the special regimes. The special regimes are divided into two groups: exemption regime and simplified taxation regime. The important thing is that the coexistence of different regimes in the same economy creates a series of distortions that cause the VAT to cease to act in its original form, i.e., as a consumption tax and become a tax on production. Another consequence of the special regimes is the occurrence of situations in which the government has to refund VAT to economic agents.

WHAT ARE EXEMPTIONS?

Exemptions are situations in which a sector, a company or a product is exempted from the obligation to pay VAT. In Mozambique there are several forms of VAT exemptions to be highlighted:

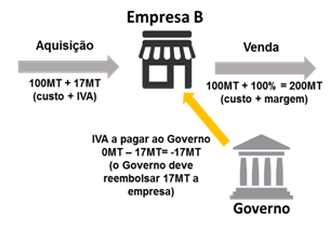

- Simple exemptions: means that you do not liquidate the tax on sales and do not deduct the tax on purchases. An illustration follows:

The firm pays VAT on acquisition (it does not deduct it) but cannot charge it on sale because of the exemption. VAT thus becomes a cost that the company passes on through the price.

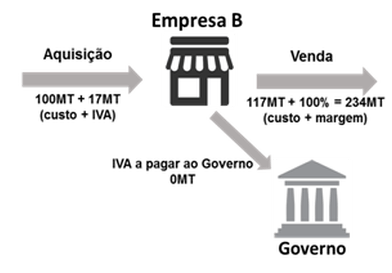

Full exemptions: means that you do not assess the tax on sales and deduct the input tax on purchases, giving rise to a VAT refund. An illustration follows:

The company does not pay VAT on the purchase (deducts) and does not charge it on the sale due to complete exemption. The firm is entitled to a refund of the VAT it paid on the purchase and did not recover on the sale.

With the examples above we can see that exemptions create distortions that change the nature of VAT. When the tax ceases to be a consumption tax and starts to burden production, economic agents can change production decisions by choosing to purchase inputs and produce goods that minimize taxation.

Another consequence, illustrated in figure 3, is the increase in the price of the final good. So far the examples presented have assumed that the VAT can always be passed on to the next agent in full without consequence. In reality this is not always the case since a price increase can have an effect on the purchasing decision (in the case of substitute goods).

The special regimes also add to the complexity of VAT management (both by firms and by the Government). Just think of a situation where a supply chain may be composed of dozens of firms (each with its own VAT regime) supplying several products (each with its own VAT regime). To complicate matters further, a product may be composed of both inputs that are subject to VAT and inputs that are exempt.

Finally, as we see in Figure 4, exemptions also create refund situations that cause the government to bear part of the VAT, a situation that can have a negative effect on the economy.

WHEN DO REFUNDS OCCUR?

Refunds occur when the assessed value results in a credit for a company. Here are some examples that generate refund situations:

- Firms that import materials and/or purchase products and services subject to VAT. These companies process the products into finished goods. However, if the finished products are exempt, the firm cannot recover the VAT through the sale;

- Some companies are exempt from VAT (usually a tax break to attract investment). As such, these firms do not pay the VAT charged by their suppliers (who are subject to VAT);

- Suppliers in turn pay VAT on their inputs but cannot recover it through VAT charged on sales;

- Exporting companies that purchase goods subject to VAT but then cannot recover the VAT on sales, because the export is exempt from VAT;

- Refunds, under normal conditions, should have no impact on economic agents and should only have an effect on state finances;

system is not fully functioning. Non-refunding and/or delayed refunds have negative consequences on economic activity:

- Firms stop supplying exempt firms and exempt products;

- Firms add the value of non-refunded VAT to their costs, thereby increasing the price level;

- Exporters add the value of non-refunded VAT to their costs, thereby reducing the competitiveness of their products;

- In summary, in an efficient VAT system, the tax only falls on final consumption, and economic agents along the chain have no impact (other than the administrative burden of managing the VAT);

- The introduction of exemptions distorts the VAT and turns it into a tax on production to be absorbed by firms (or passed on to the consumer through prices) or reimbursed by the government;

- These distortions are further aggravated when the refund system does not work;

- There is generally some pressure to exempt certain sectors and products from VAT;

- It is important that economic agents and the Government understand the impact of these exemptions to understand if the exemption really has the desired effect;